SEPTEMBER 2025

‘Living Archives’ in Modern Scotland

It’s the 1st of September, and that can only mean one thing for us up here in Edinburgh: the end of the Festivals Fringe. Though it has made our commutes a bit of a nightmare, we love the festivals and all the art and culture they bring to our lovely city.

This year, alongside all the comedy and theatre, I attended an event at the International Book Festival about heritage and archiving, entitled ‘Beyond the Archives with Ewan Morrison & Doug Johnstone’. This talk explored writers and their experiences being part of living archives, and how institutions now look to preserve the works and artefacts of writers while they are still living.

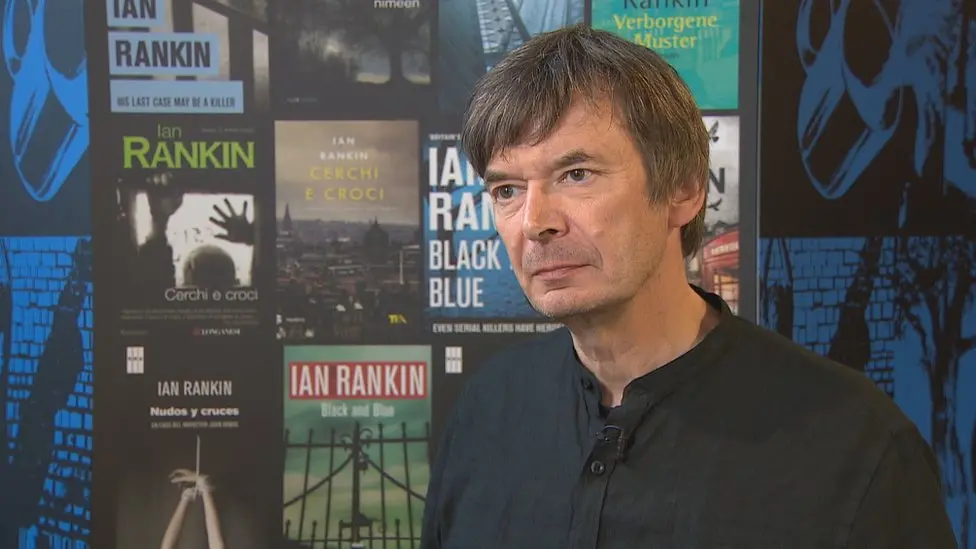

This is an increasingly popular method of preservation in the 21st century; Scottish authors and poets like Jackie Kay and Ian Rankin have, in the past few years, donated their notes, letters, manuscripts etc. to “the best of all homes” (Jackie Kay, 2024): the National Library of Scotland, so that fans and researchers can explore their careers and works contemporaneously.

“The library has seemed like a friend ever since, so it seems fitting – as well as a thrill and an honour – that my archive should find a permanent home there.”

Ian Rankin, BBC News, 2019

The event I attended raised interesting questions around a ‘living archive’ and how a writer might feel about donating their possessions to a library or archive, which I’d like to explore today.

Why is it important to create living archives?

At the event, Scottish writers and archive subjects Doug and Ewan expressed how their creative processes are preserved in real time using a living archive. Note scraps with potential novel titles, coffee-stained manuscripts, letters to and from publishers; they all capture what it is like to be a 21st century Scottish writer, and anyone with interest in or aspirations towards such a career can look to these items for insight into the creative process and the fiction industry without editorialization or the distance of history.

In addition to this, authors can influence how they contribute to cultural memory whilst they are still alive. We can minimise biased third parties only donating parts of collections, or vital pieces of information lost to history, if the person of note is still alive to make their own contributions. Of course, people can curate their own donations, but this errs into matters of ownership, which I’ll touch on later.

How do we navigate technological advancements in archiving?

Digital archives are becoming a necessity, and living archives are no different. Most correspondence is via email or online messaging, and, when it comes to fiction writing, most stories are typed up and edited digitally rather than the analogue method of scribbled-upon manuscripts. Moreover, archives themselves are becoming more digital, digitising documents as we do here at UK Archiving to make heritage materials easier to share and search.

Additionally, archives in the 21st century are using digital tools to preserve culture and history that previously could not have been preserved in their raw form. Alongside the collections of writers like Kay, Rankin, Morrison, and Johnstone, the National Library of Scotland is collating audio and moving image archives to preserve them without the need to convert into a physical format. This is not unique to Scotland either, archives across the world are using video, audio, and even augmented reality as tools for preservation.

There were brilliant discussions at the Book Festival event about the concerns writers and archive subjects have about how their works will be remembered in an age of ‘AI slop’ and web scraping. The conversation around the merits and risks of AI are beginning to extend to the heritage industry, with some archiving initiatives embracing AI as a tool to create more interactive and imaginative preservation experiences.

Ewan and Doug both discussed how digital versions of their work have been pirated and scraped online, and how generative AI can and does invent inaccurate information about their lives and work. They were, understandably, incredibly concerned about how their works and information could be stolen and misused by the radical accessibility that we’re all adapting to online.

Here we alight on the question that interests me most profoundly about a ‘living archive’.

What does it mean to own an item?

Doug expressed at the event how odd it was to have to make a booking to view an item that once sat on his desk, now needing archival equipment and supervision to view the same object that was once his possession. Those post it notes and scribbled-in notebooks were now publicly available and publicly owned by an archive. But others find this preservation process reassuring and a source of pride:

“It’s a comfort and an honour to know that years after I’m gone people will still be able to have a good old rummage amongst my things.”

Jackie Kay, National Library of Scotland, 2024

At UK Archiving we take part in the process of preserving items from all sorts of places, eras, and collections. Some of these items were once personal possessions: hand-written letters, books with scribbles in the margins, photographs that capture intimate moments from people’s lives.

Usually, the people who once owned these objects are long gone; their items are now a part of history. But now, with the onset of living archives and intentional curation, the possessions of the living can be donated and preserved as objects for public display and examination.

For one reason or another, the reverence that people feel when viewing archival materials often comes from the age and history of the object; it is a tangible connection between the present and the past. The items that we own are not as exciting. They seem mundane. Unremarkable. But one day they might become a lost scrap of history, placed into a museum for future generations to look at with awe.

What I find so intriguing about living archives are their intentionality. We are more aware than ever of the impact we and our possessions leave on the world. So why not be intentional about what we preserve, rather than leaving future historians whatever scraps they can salvage? We can be sure that writers like Jackie Kay, Ian Rankin, Ewan Morrison, and Doug Johnstone are remembered.

But also, their donated possessions will leave clues about what being a writer, as well as just a person, was like in late 20th and early 21st century Scotland. And we do not have to wait to celebrate and study these possessions; living archives mean that we can celebrate the culture and heritage of today alongside the past, adding to them as we go to ensure that they will be remembered.

Resources/References

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23257962.2024.2381234#d1e527

https://artsexperiments.withgoogle.com/living-archive/?token=1756299191

https://curatinglivingarchives.network/about/

https://scotlands-sounds.nls.uk/

https://www.scottisharchives.org.uk/archives-map/scottish-screen-archive/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-48380555

https://media.nls.uk/news/jackie-kay-chooses-national-library-as-home-for-her-archive

by Amy McVeigh | 01 Sep 2025